A blog post by Chris Holden, MPhil/PhD candidate (Oxford Brookes University)

‘My heart failed within me, and I wept at the thought of being sent adrift in a far-off country.’

John Castle BURN 1:134

These are the words of the working-class autobiographer, John Castle, writing about his feelings and tears, aged 17, on being kicked out of the workhouse in 1837 for speaking up on his brother’s behalf to the Board of Guardians. He was unemployed, near penniless and sixty miles from the family home. His sense of isolation and helplessness bleed from his words, he is ‘sent adrift’, another word for a castaway. He is at that moment undoubtedly feeling lonely and yet he does not use the word. Seven or eight years later, in his famous poem ‘I Am’, the peasant poet John Clare, at the time confined to an asylum and desperately lonely similarly writes of ‘the vast shipwreck of my life’s esteems’.

At the time loneliness was a term most often reserved for describing the remoteness of a place, or simply being alone. It was rarely used in common currency to describe the condition that we recognise today as a lack of close, emotionally fulfilling, attachment to at least one other person. It is therefore difficult to apprehend how prevalent loneliness and how it was manifest in past centuries, particularly amongst the lower classes. I am especially interested in the lives of rural labouring people, those from an oral tradition who left few textual sources behind describing their emotional lives.

Nostalgic representations of rural communities of old would have us believe that people were surrounded by friends and family always there in times of trouble to talk to and extend a helping hand. Many of these accounts, be it biographical or fictional, come from a distinctly middle-class perspective where childhoods were long and secure. My research seeks to assess to what extent concepts fundamental to most human beings’ wellbeing, such as family, community and belonging existed during the socially and economically transformative years of the long nineteenth-century (c.1780-1914).

Did the hardship of life, where hunger, illness and death in the family were far more commonplace than now generally inure people to the worst pain of loneliness? Equally was there something about the cohesiveness of village life and perhaps greater religious commitment (which certainly was a sustaining factor in John Castle’s life story) that acted as a palliative and if so, what lessons might we be able to take from the past that will help build a society capable of reversing the so-called ‘epidemic of loneliness’?

Professor Burnett’s two books on working class autobiography Useful Toil and Destiny Obscure provided tantalizing glimpses of the sort of life stories I was interested in; lives replete with abject poverty, violence, separation and loss (parents, siblings and homes). What is amazing is how matter-of-fact so many of these accounts of privation and hopelessness and how little mention of the words directly synonymous with ‘loneliness’ appear in the texts. A cultural historian of the emotions though is encouraged to look at the clusters of feelings expressed and overlaying an autobiography, the ‘silences’, the rhetorical language and the metaphors used by the authors and then so much more of their emotional lives is brought into the light.

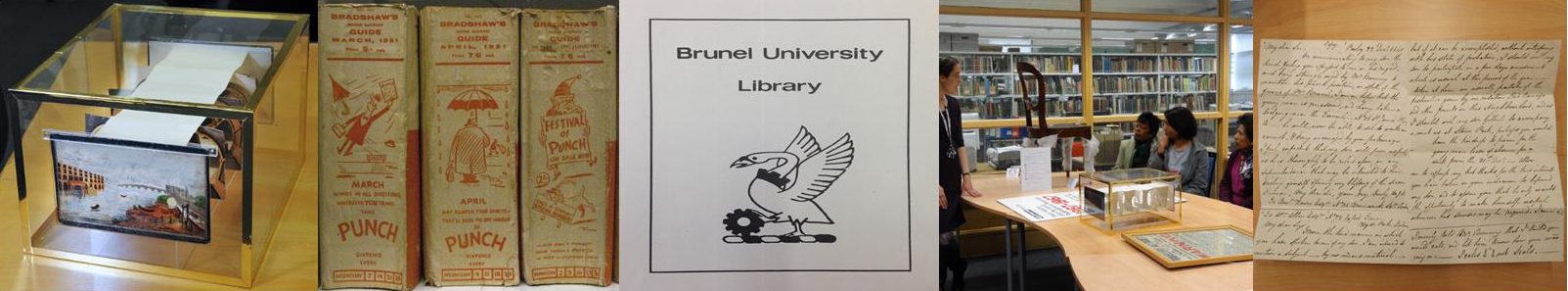

Therefore, I was delighted to discover that the Burnett Archive filled with so many more unpublished autobiographical accounts, including the aforementioned John Castle, although understandably closed to visitors during the pandemic, remains available digitally to researchers and I have been able to thus far gain remote access to many more of the treasures that Professor Burnett’s scholarship and persistence had unearthed.

I highly recommend anybody interested in any aspect of British cultural and social history of the last 250 or so years to have a look at this exceptional archive. The lives of those now long dead were remarkable for their fortitude in the face of so much distress and suffering and I hope that others will look at ways of revealing other aspects of their stories.