A blog post by Raphaëlle Goyeau, a student volunteer in Special Collections. Raphaëlle is a native French speaker who used poetry to help her learn English.

On 21 March, we are once more celebrating World Poetry Day. It happens that it is also, since 2016, Education Freedom day – an observance in honour of all free knowledge and educational software online. To celebrate both, let us introduce Bill Griffiths and share some of his legacy by learning a bit of Old English through his poetry translations.

The Battle of Maldon, and its beautifully bound version, tell us of the real 991 battle between Anglo-Saxon and Vikings – which does not end well for the Saxons. A large part of the poem has been lost, but what remains is now available in Modern English. Below, the original version next to Griffith’s one.

Het þa hyssa hwæne hors forlætan, He-bade then warrior’s each horse to abandon

feor afysan, and forð gangan, Far-away to drive and forward to-march,

hicgan to handum and to hige godum. To-think on hands and on mind worthy,

Þa þæt Offan mæg ærest onfunde, When it Offa’s kinsman first discovered

þæt se eorl nolde yrhðo geþolian, That the earl would-not lack of spirit tolerate

he let him þa of handon leofne fleogan He allowed then from his wrists cherished to-fly

hafoc wið þæs holtes, and to þære hilde stop;

Hawk towards the woods, And to the battle advanced;

As you can see, several words can be used to identify where in the poem we are when looking at the translation. Other words can probably be translated through the context. Can you see what “gangan” means? What about “leofne” or “hilde”?

The Phoenix, on the other hand, was itself a translation when Griffiths made the Old English version into a modern alliterating text. It would be an adaptation of the Latin poem De Ave Phoenice, which tells us of the mythical Phoenix, resident of the Garden of Eden whose life cycle never ends. As in Greek Mythology, the bird grows old, dies, but rises again from the ashes. It appears first in the first verses at the beginning of the part two, here in Old English:

ðone wudu weardaþ wundrum fæger

fugel feþrum strong, se is fenix haten.

þær se anhaga eard bihealdeþ,

deormod drohtað; næfre him deaþ sceþeð

on þam willwonge, þenden woruld stondeþ.

And here, by Mr. Griffiths:

This is the FOREST GUARDED by a GLORIOUS BIRD

BEAUTIFUL, and brave of FEATHER “PHOENIX” is CALLED

It KEEPS its HOME HERE, in SOLITUDE

SWEETLY DWELLING; for DEATH never TOUCHES,

While TIME ENDURES that DELIGHTFUL SPOT

Some words can be more or less easily identified. For example, it seems logical that the Old English “Fenix” would have given us the modern “Phoenix”, and the modern “death” can be guessed by the shape of “deaþ”. Others, such as “anhaga”, can reaquire a dictionary, which would tell you that it means “solitary”, or “recluse”.

Having both texts in hand, could you guess the meaning of “haten”, “wudu” or “woruld”? Answers below!

From Battle of Maldon

Gangan: to go, here “to-march”

Leofne: dear, beloved, here “cherished”

Hilde: war, battle, here “battle”

From The Phoenix

Wudu – Wood, tree, here “forest”

Haten – named, here “called”

Woruld – cycle, eternity, long period of time, here simply “time”

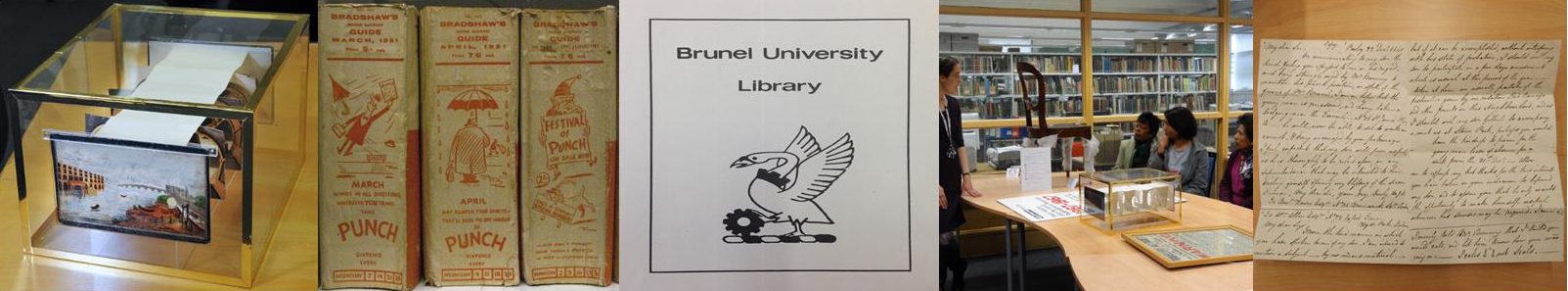

You can find these texts and much more in our Bill Griffiths Archives