Our reading room is open Monday – Friday by appointment only and subject to staff availability. Please contact us to make an appointment.

Due to our recent relocation, we are only able to offer a limited enquiry service at the moment.

Our reading room is open Monday – Friday by appointment only and subject to staff availability. Please contact us to make an appointment.

Due to our recent relocation, we are only able to offer a limited enquiry service at the moment.

Special Collections will be closed to all users from Monday 5 July until Monday 4 October 2021. This is due to the relocation of Brunel University Archives to join Special Collections in the University Library.

To enable staff to focus on this work our enquiry service is also suspended. It may still be possible to supply copies of digitised items from the Burnett Archive, but there will be delays in responding.

We sincerely apologise for the short notice, but it is beyond the control of Records, Archives and Special Collections staff. We look forward to welcoming you back from October onwards.

We’re taking part again this year in #Archive30 a social media campaign organised by the Archives and Records Association Scotland and taken up by archives and special collections around the world.

There is a daily theme for each day in April, highlighting various aspects of our wonderful collections.

You can follow on Twitter using the hashtag #Archive30 and our Twitter feed is @BrunelSpecColl, Brunel University Archives is @BrunelUniArch

The Special Collections reading room has reopened, for Brunel staff and students only. It is by prebooked appointment, Wednesday – Friday 10am – 4.15pm, closing for an hour at lunchtime. You can check when we are open on the library guide. Places must be prebooked, at least three working days in advance, by emailing special.collections@brunel.ac.uk

To comply with social distancing measures, we’ve reduced the number of seats to three, one of which has a power socket. You will have a seat and locker reserved for you. As usual bags, coats etc must be left in a locker. If you need to cancel or change the date of your visit, please let us know to enable someone else to have the place. Any material used will be quarantined between visits and you will need to let us know when you book what you would like to see when you visit.

When you arrive at the Welcome Desk, you will need your ID card. This is to enable us to meet government track & trace requirements using our entry/exit turnstiles. In line with government guidance, face coverings are mandatory for all Library users. This is subject to the usual exclusions for medical reasons. Face coverings are available to purchase from the vending machine in the Bannerman Foyer or from Costcutter. There is further information here about other services provided by the library and information about campus catering facilities here.

For those who are unable to visit, Special Collections still offers a reprographics service – please email us with your enquiries.

The university Easter break is Saturday 27 March – Tuesday 6 April 2021 inclusive. Special Collections will be closed for this time, and any enquiries received will be answered from 7 April 2021 onwards.

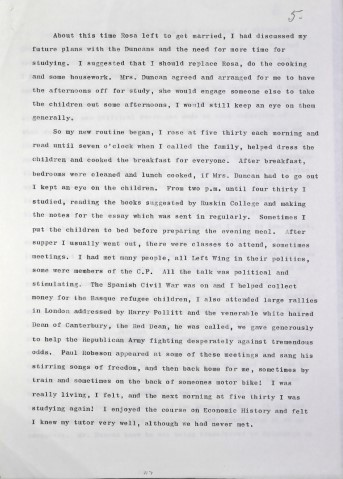

A blog post by Chris Holden, MPhil/PhD candidate (Oxford Brookes University)

‘My heart failed within me, and I wept at the thought of being sent adrift in a far-off country.’

John Castle BURN 1:134

These are the words of the working-class autobiographer, John Castle, writing about his feelings and tears, aged 17, on being kicked out of the workhouse in 1837 for speaking up on his brother’s behalf to the Board of Guardians. He was unemployed, near penniless and sixty miles from the family home. His sense of isolation and helplessness bleed from his words, he is ‘sent adrift’, another word for a castaway. He is at that moment undoubtedly feeling lonely and yet he does not use the word. Seven or eight years later, in his famous poem ‘I Am’, the peasant poet John Clare, at the time confined to an asylum and desperately lonely similarly writes of ‘the vast shipwreck of my life’s esteems’.

At the time loneliness was a term most often reserved for describing the remoteness of a place, or simply being alone. It was rarely used in common currency to describe the condition that we recognise today as a lack of close, emotionally fulfilling, attachment to at least one other person. It is therefore difficult to apprehend how prevalent loneliness and how it was manifest in past centuries, particularly amongst the lower classes. I am especially interested in the lives of rural labouring people, those from an oral tradition who left few textual sources behind describing their emotional lives.

Nostalgic representations of rural communities of old would have us believe that people were surrounded by friends and family always there in times of trouble to talk to and extend a helping hand. Many of these accounts, be it biographical or fictional, come from a distinctly middle-class perspective where childhoods were long and secure. My research seeks to assess to what extent concepts fundamental to most human beings’ wellbeing, such as family, community and belonging existed during the socially and economically transformative years of the long nineteenth-century (c.1780-1914).

Did the hardship of life, where hunger, illness and death in the family were far more commonplace than now generally inure people to the worst pain of loneliness? Equally was there something about the cohesiveness of village life and perhaps greater religious commitment (which certainly was a sustaining factor in John Castle’s life story) that acted as a palliative and if so, what lessons might we be able to take from the past that will help build a society capable of reversing the so-called ‘epidemic of loneliness’?

Professor Burnett’s two books on working class autobiography Useful Toil and Destiny Obscure provided tantalizing glimpses of the sort of life stories I was interested in; lives replete with abject poverty, violence, separation and loss (parents, siblings and homes). What is amazing is how matter-of-fact so many of these accounts of privation and hopelessness and how little mention of the words directly synonymous with ‘loneliness’ appear in the texts. A cultural historian of the emotions though is encouraged to look at the clusters of feelings expressed and overlaying an autobiography, the ‘silences’, the rhetorical language and the metaphors used by the authors and then so much more of their emotional lives is brought into the light.

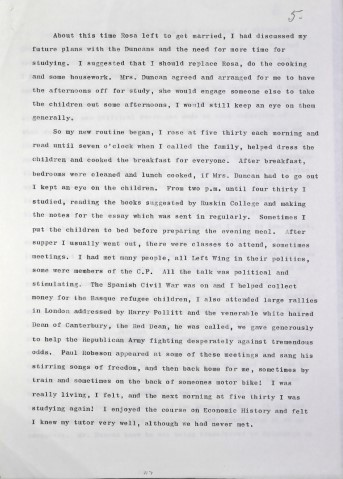

Therefore, I was delighted to discover that the Burnett Archive filled with so many more unpublished autobiographical accounts, including the aforementioned John Castle, although understandably closed to visitors during the pandemic, remains available digitally to researchers and I have been able to thus far gain remote access to many more of the treasures that Professor Burnett’s scholarship and persistence had unearthed.

I highly recommend anybody interested in any aspect of British cultural and social history of the last 250 or so years to have a look at this exceptional archive. The lives of those now long dead were remarkable for their fortitude in the face of so much distress and suffering and I hope that others will look at ways of revealing other aspects of their stories.

Special Collections remains closed to readers and will be closed completely over the Christmas/New Year period, from 18 December 2020 to 7 January 2021 inclusive. We will be available to answer enquiries from Friday 8 January onwards. You can get in touch with us by emailing special.collections@brunel.ac.uk.

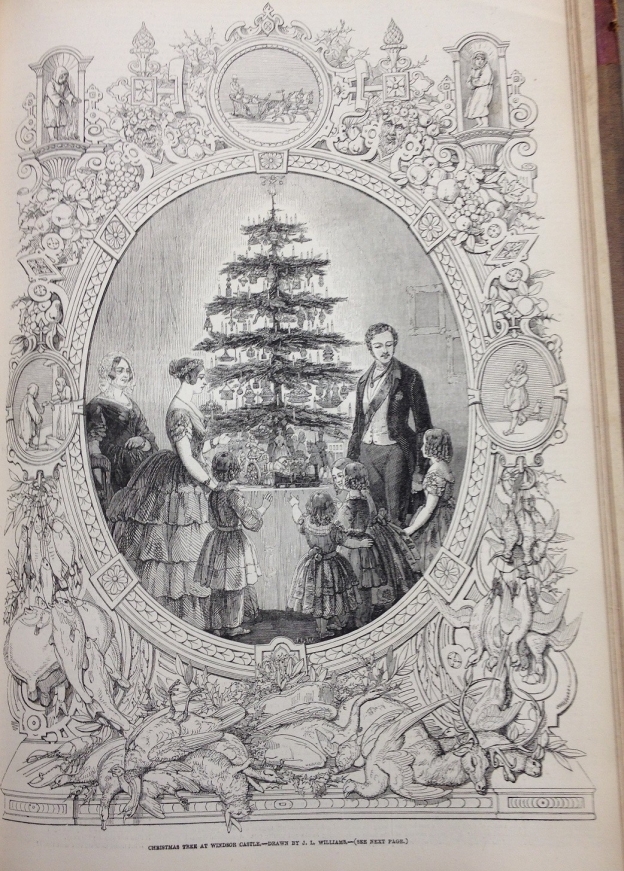

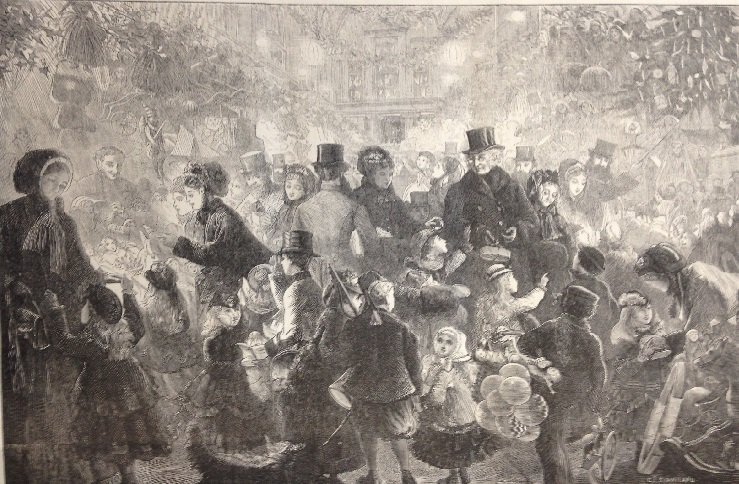

In the meantime, we may not be able to celebrate like this this year, but we wish all of our readers and volunteers a safe and enjoyable Christmas and we hope to be able to see you before too much longer.

Brunel University has loaned a manuscript from the Burnett Archive of Working Class Autobiographies, part of Records, Archives and Special Collections within Library Services, to an exhibition at the British Library. The exhibition, Unfinished Business: the fight for women’s rights, explores how women have fought, throughout history and up to today, to assert control over their bodies, minds and voices in the face of legislative, economic and cultural practices which have rendered them unequal to men. The exhibition interrogates the lives of women past and present and makes explicit the connections between the continued battles for equality today and struggles in the past.

The manuscript we have loaned is by Winifred Relph, who was born in 1912. Her account narrates her work as a domestic servant, and her later enrolment at Hillcroft College for Women, conveying how higher education institutions for working class women helped many of them to progress. Relph’s account is a very vivid memoir that highlights the difficulties of juggling demanding work with getting an education.

The exhibition is at the British Library between 23 October 2020 and 21 February 2021. Exhibition tickets must be booked in advance on the British Library’s website.

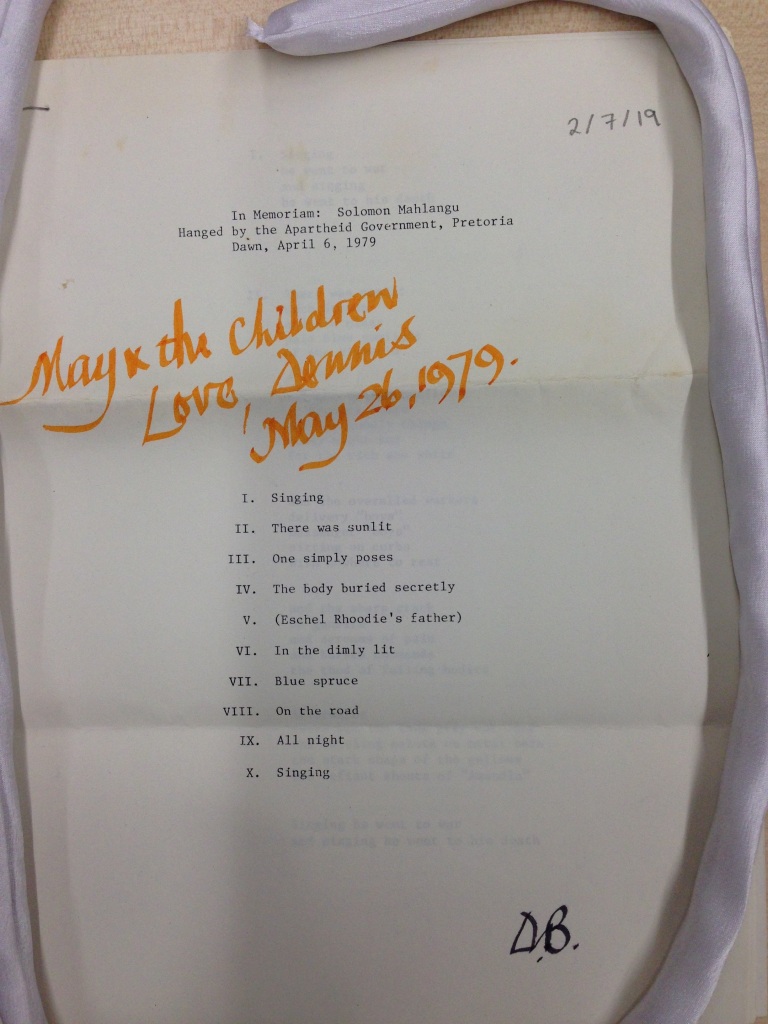

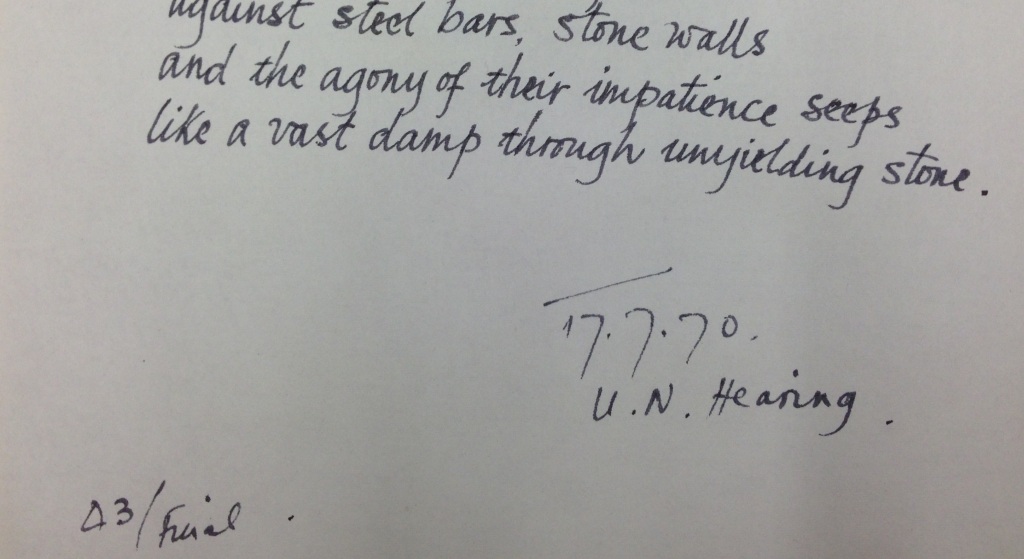

As we mark Black History Month we’re highlighting historical material from Special Collections. This time the spotlight is on Dennis Brutus.

Dennis Brutus (1924-2009) was a poet and human rights activist who grew up in South Africa. He taught in a high school until he was dismissed for activism against apartheid, and he became instrumental in the movement against racism in sport. He was imprisoned and, on release, forbidden from teaching, publishing his writings, continuing to study law, and attending political meetings.

His poems reflect his frustrations and sadness at the political environment, and are frequently concerned with the sufferings of fellow black or mixed-race people.

One poignant set of poems on this topic is In Memoriam: Solomon Mahlangu, published in 1979. Solomon Mahlangu was a South African who was hanged by the apartheid South African government in 1979 after a controversial verdict finding him guilty of murder, and despite the intervention of the UN. The deaths were caused by another man, who was not considered fit to stand trial, and Mahlangu was found guilty on the understanding that he had had a “common intent” with the other man. The booklet begins, and ends,

“Singing

he went to war

and singing

he went to his death”.

The copy of this collection held at Brunel has a handwritten dedication to Brutus’ wife and children.

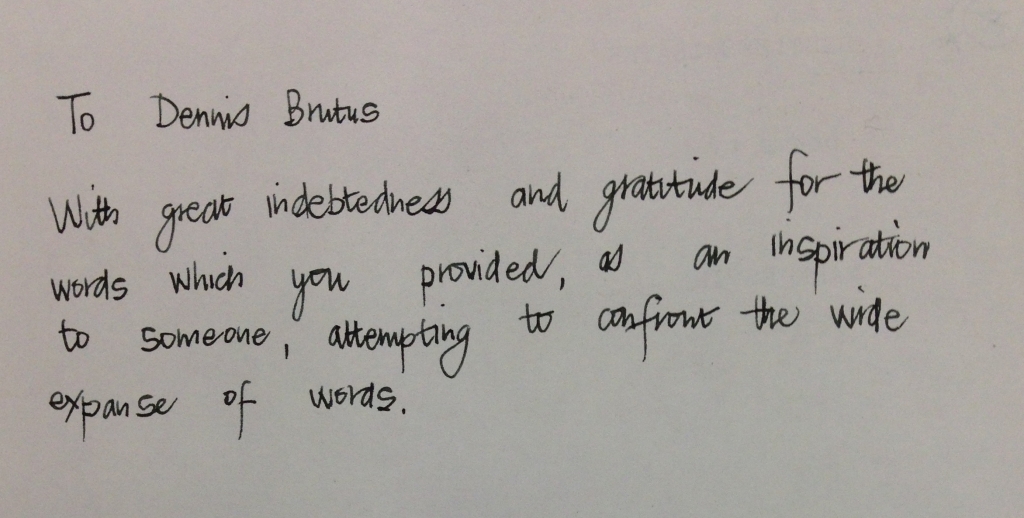

Another published booklet of poems held in the Dennis Brutus Collection is Thoughts Abroad, by Dennis Brutus but published under the pseudonym John Bruin in order that it could be published in South Africa, where Brutus’ work was banned. This copy has been updated to attribute the work correctly and explain more about Brutus and his work.

There also handwritten poems and drafts by Dennis Brutus, and various works by other poets. The copy of Restless Leaves, a booklet of poems by Mark Espin, is dedicated to Dennis Brutus in thanks for the inspiration he provided.

On 15 June 1945 the Family Allowances Act was enacted. This was an important step in the fight for economic independence for women. The original campaign, led by Eleanor Rathbone, said it was of “immense importance” that the allowance be paid to mothers, but when, in February 1945, the Family Allowances Bill was published, it stated that the money would belong to the father. This led to a cross-party rebellion, and the bill was amended to pay the money to mothers. You can see the Act on the Parliamentary Archives website and find out more about Eleanor Rathbone.

The Act came into operation the following year, on 6 August 1946, and was the first time child benefit was provided in the UK. An allowance of five shillings a week was paid for each child in a family, other than the eldest. It was payable whilst the child was of school age, up to the age of eighteen, if apprenticed or in full-time school education.

Our Burnett Archive of Working Class Autobiography includes some accounts that mention Family Allowance, although some of these are more negative. The collection as it was originally brought together has content up to 1945, so many of the writers experienced growing up before family allowances and have the attitude that their parents coped without it.

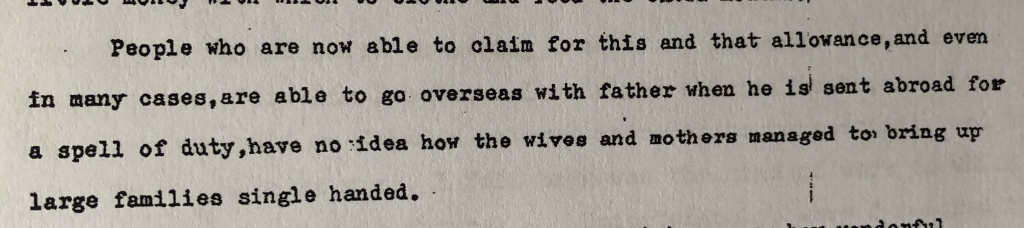

For example, Dora Hannan, looking back from the 1980s on her early life, when her father was at sea with the Royal Navy for years at a time, writes:

“People who are now able to claim for this and that allowance … have no idea how the wives and mothers managed to bring up large families singlehanded”

BURN 2:357 Hannan, p. 1

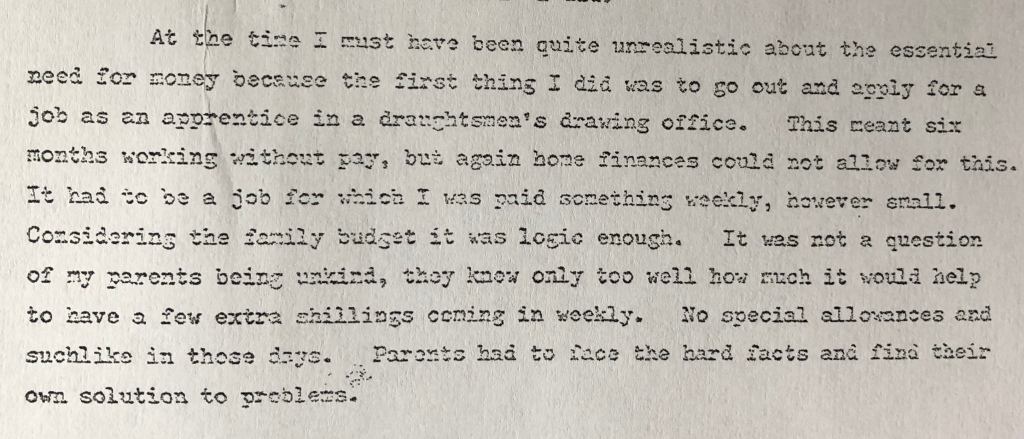

In 1919, long before Family Allowance, Stanley Rice wanted to take on an unpaid apprenticeship but was unable to, as his parents couldn’t afford to support him without a wage:

“It was not a question of my parents being unkind, they knew only too well how much it would help to have a few extra shillings coming in weekly. No special allowances and suchlike in those days. Parents had to face the hard facts and find their own solutions to problems“

BURN 2:661 Rice p. 10

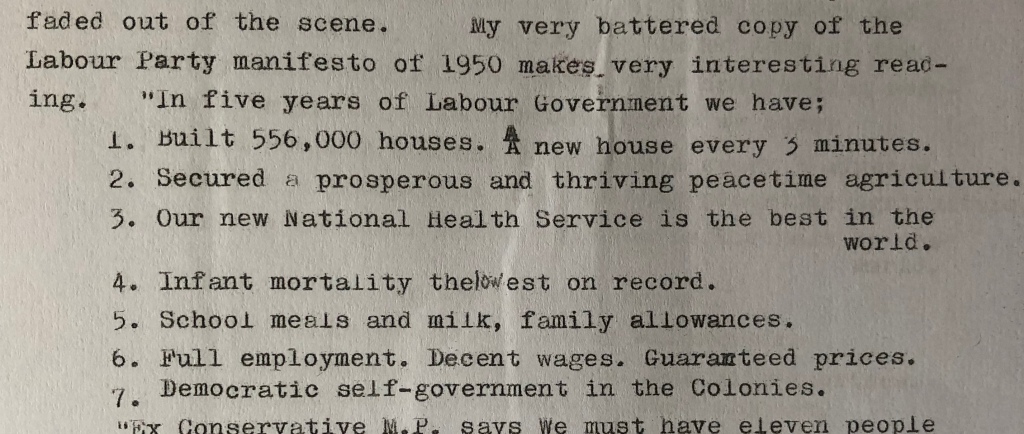

And in 1950 Margaret Perry comments on her “very battered copy” of the Labour Party manifesto:

“In five years of Labour Government we have: Built 556,000 houses. A new house every 3minutes. Secured a prosperous and thriving peacetime agriculture. Our new National Health Service is the best in the world. Infant mortality the lowest on record. School meals and milk, family allowances. Full employment. Decent wages. Guaranteed prices. Democratic self-government in the Colonies“

BURN 2:606 Perry p. 34

Over the years the terms of the Family Allowance were changed, including in 1952 an increase of three shillings a week to combat poor nutrition and extended to all schoolchildren in 1956 in an attempt to keep children in education. In 1977, child benefit was phased in, which still exists today.

One of a series of blog posts written by Brunel’s creative writing students, inspired by the Burnett Archive of Working Class Autobiographies.

Some individuals may find the topic covered in this blog post distressing. Should you require support please contact:

Brunel Students: Student support and welfare team

Non-Emergency NHS Helpline: 111

Samaritans: 116 123 (open 24 hours)

It’s getting faster, moving faster now, it’s getting out of hand. On the tenth floor, down the back stairs, it’s a no man’s land. Lights are flashing, cars are crashing, getting frequent now, I’ve got the spirit, lose the feeling, let it out somehow.

‘Disorder’, Joy Division, Closer. Factory Records, 1979 (lyrics Ian Curtis)

Such lyrics are electrifying and vivid, I am a rather electrifying and vivid person myself, so is my fellow epileptic bredrin, Ian Curtis of Joy Division. Divided between joy and sympathy, I’m unsure whether this character flaw is well and truly beneficial. I enjoy the freedom pass which allows me to journey through London without any incurred costs, but I cannot pass through true freedom (whatever that is). My brain is chained to this neurological defect, it infects my whole life. I enjoy the sympathy I get from women, but I know they don’t like me for me. I am their baby; I am not their baby. Why would they like the things I am called every day: a retard, a mong and a windowlicker? Why would anyone? Male or female. Who would? I don’t want to ruin anyone’s reputation, but I do because I’m me. Why is that? Oh wait, it’s because I have epilepsy. Most of the people in my life know nothing about it and seem to think my trigger is flashing lights. How cliched. What makes you think I can’t play videogames and go to concerts? What makes you think I can’t get drunk? What makes you think I’ll have a seizure straightaway whenever you repeatedly flash your iPhone torch in my eye? People are inconsiderate morons.

I want to be accepted, but I have to constantly justify myself. I have to prove myself, but I’m not sure how to improve when I have this condition. Although my father has good intentions, I am jailed and cannot move out in case it worsens. Maybe I’m jailed because of my epilepsy, maybe I am not, although it certainly feels like it. I am certain I can still drink, smoke, lift and run, but each one is dangerous. I just drink because…I just do. No that’s not it. It’s because I need acceptance from my friends and to seem more ‘adult’ to others. Mine is a Heineken, thank you. I smoke to help me concentrate, yes, I am aware it could kill me, however I would rather addiction kill me than the epilepsy, it means I can assume control. There is a 1 in 1000 chance of dying whenever I have a seizure, even if I take my lamotrigine, I am aware of it. If I have a seizure and don’t take my lamotrigine, the chance of death taking me by the hand increases to 1 in 150. I no longer lift despite how much stronger it made me; I don’t feel any stronger. I am strong physically, I can lift heavily to some extent, but I’m not strong enough to ask for someone to spot me, it would be far too awkward. I wouldn’t feel like I’m in control. Besides, who would want to help someone who isn’t ‘that disabled’ anyway? If a heavy weight fell on me, I would no longer have any sort of control left, I would be known as ‘that disabled guy.’ It became catch-22 ever since epilepsy caught me at age 22. I can still run, I guess. I used to run 5ks with ease, but I was always scared of having a seizure. Isolated from everyone else, left to foam at the mouth and have blood crawl down from my head to my lips, I can no longer take the risk. I am well and truly out of control.

Hmmm. Maybe I’m not as limited as I say I am. Am I just lazy? Have I become too complacent because of the epilepsy? Well, what feels like my brain is being electrocuted and constantly fried seems to force me into laziness and craziness. The gargling people hear whenever I have a seizure sounds like mouthwash keep continually swirling around and around in my mouth. I once had a seizure when I was partway through a sentence when talking to my friends on Discord. One of the women in the group chat told me to ‘shut the f*** up,’ although we were both oblivious to what happened. I was surprised she begged for my forgiveness, but I forgave her despite being unsure of what I was forgiving her for. I’d had no idea a seizure had occurred. How embarrassing.

I don’t want to keep on taking these pills, but I have to. I don’t want keep on having these existential crises, but I have to. I don’t wish to keep talking about my epilepsy because of how stigmatised it is, but I have to. Why do I have to talk about it? Well, people are going to have to be aware of what it is and aware of what to do when a seizure occurs. Why do I have to keep on talking about it? Well, I want to make my mark on public consciousness, specifically through writing. I have no other choice. Epilepsy is a contradictory disability, it can control you, but you can also control it. I will control it; I will beat any and all expectations expected of such a life altering disability. Maybe I shouldn’t call it epilepsy and instead call it pepilepsy for I must ensure I’m lively . . . You must be mad if you think I am a retard, maybe you are a retard yourself. We shall wait and see who prevails.

© Mark Jobanputra, 2020. All rights reserved.

‘Pepilepsy’ was inspired by ‘Fit For Anything’ by Wally Ward (2:798), in the Burnett Archive of Working Class Autobiography, Special Collections, Brunel Library, Brunel University London.

Author’s Note:

I decided to write Pepilepsy with the intention of highlighting the way(s) epilepsy, a frankly niche and misunderstood condition, has the ability to shape one’s life in a most negative manner. I am writing from my own personal experience having been diagnosed with epilepsy at age 22 (I am 26 as of writing this piece). I wouldn’t wish such a cursed condition on anyone, yes, even you. Although I personally feel cynical about this condition leaving me someday, Wally Ward’s memoir ‘Fit for Anything’ was the driving force in exploring epilepsy and the potential for ‘overcoming’ in this piece of writing about said neurological condition.

Mark Jobanputra is currently studying for an MA Creative Writing at Brunel University London. He tweets at @madstillainy